By Staff Correspondent

Kenya is facing a moment of reckoning over one of the most disturbing corporate scandals in its recent history, a scandal that exposes how betting revenues, shell companies, and complicit directors were allegedly used to launder hundreds of millions of shillings while regulators and prosecutors watched from the sidelines.

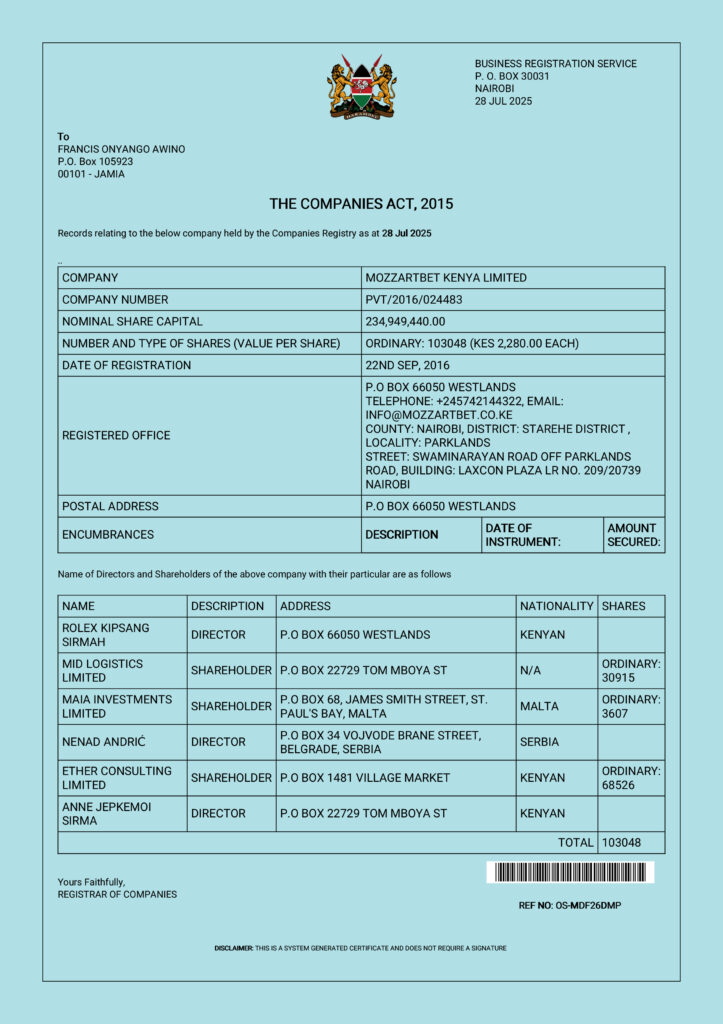

At the centre of the storm are Mozzart Bet Kenya and Kimaco Connections Limited, companies that courts have now firmly linked to a sophisticated money-laundering scheme involving more than KSh 576 million.

This is not speculation. These are findings of fact by the High Court of Kenya and the Court of Appeal.

In 2020, Mozzart Bet Kenya claimed it had contracted Kimaco Connections Limited to provide software services worth KSh 256 million. On paper, it looked like a standard commercial transaction. In reality, investigators would later establish that Kimaco had no technical capacity, no staff, no systems, and no track record to deliver services of such magnitude.

Even more troubling, Kimaco had been filing nil tax returns with the Kenya Revenue Authority, effectively declaring that it had no meaningful business activity at all.

So how does a dormant company with no capacity land a quarter-billion-shilling software deal with one of the country’s largest betting firms?

The courts answered that question bluntly: it was never a genuine contract.

Investigations by the Assets Recovery Agency (ARA) revealed a pattern that anti-money-laundering experts know too well.

Funds were paid to Kimaco before any valid contract existed, quickly transferred through third-party entities such as Pescom Kenya Limited, and ultimately traced back to directors and affiliates of Mozzart Bet itself.

This is what investigators call layering—a deliberate attempt to disguise the origin and ownership of illicit funds.

On 1 April 2022, High Court Judge James Wakiaga delivered a devastating ruling, declaring KSh 304 million to be proceeds of crime under the Proceeds of Crime and Anti-Money Laundering Act (POCAMLA). The money was frozen, and the scheme laid bare.

Perhaps the most audacious twist came when Mozzart Bet attempted to sue Kimaco Connections, portraying itself as a victim seeking to recover lost funds.

The courts were unimpressed.

Judges found that Mozzart Bet was not an innocent party, but an active participant in the scheme through its directors and its affiliate, Open Skies. The civil suit was dismissed, seen for what it was: an effort to launder a criminal transaction through the courts.

In May 2025, the Court of Appeal—Justices Toiyott, Ochieng, and Muchelule—upheld the forfeiture of the funds, confirming that the transactions bore all the hallmarks of fraudulent contracting, illegal enrichment, and money laundering.

The court named individuals linked to the scandal, including:

- Musa Sirma, former legislator and director

- Sasa Melentijevic, Managing Director of Mozzart Bet Kenya

- Justice Charumbira, an executive connected through Open Skies

The verdict left no legal ambiguity. The money was criminal. The scheme was deliberate.

And yet, despite binding court judgments, no high-profile criminal prosecutions have followed.

No arrests.

No charges.

No accountability.

This silence raises an uncomfortable question: Is corporate crime treated differently when it involves powerful firms and politically connected individuals?

Under Kenyan law, the conduct exposed in this case squarely fits offences under the Penal Code and POCAMLA, including conspiracy to defraud and possession of proceeds of crime. The evidence threshold has already been tested and upheld in court.

What remains is political and institutional will.

This scandal goes beyond Mozzart Bet or Kimaco Connections. It exploited M-Pesa pay-bill infrastructure, meaning ordinary Kenyans—placing legal bets—unknowingly contributed to a laundering operation.

If left unpunished, it sends a dangerous signal: that Kenya’s betting industry can be used as a cash-washing machine, and that shell companies can siphon millions without consequence.

That is not just corruption. It is economic sabotage.

Legal experts now argue that Kimaco Connections Limited should be wound up immediately under the Insolvency Act. It has no legitimate business, no assets of substance, and a documented history of being used as a conduit for criminal proceeds.

More importantly, the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions must act. Court judgments are not decorative documents. They are calls to enforcement.

The Mozzart Bet–Kimaco scandal is a test of Kenya’s commitment to the rule of law. The courts have done their job. Investigators have done theirs.

What remains is the hardest step: holding powerful people accountable.

Until that happens, every Kenyan has reason to ask whether economic crime in this country is punished—or merely postponed.

Justice delayed in economic crime is prosperity denied to the people.

The Views expressed in this article are not of DNK International